Last week we talked a lot about oxytocin. This week we will focus on attachment theory and the research related to the impact of parental attachment styles, attachment styles and mental and physical health, attachment related interventions. Below you will find my notes on the topic. Each article has the bibliographic reference and most articles are available as free full-text pdfs. If you are not big on research, you can get the gist by reading the introduction and the discussion/conclusions section. (skip methodology and results)

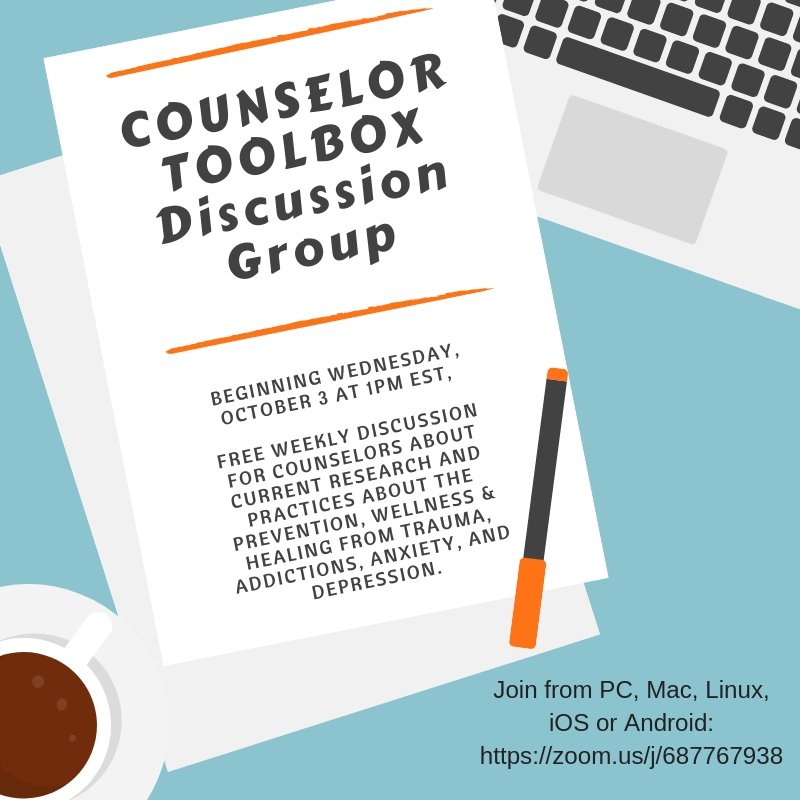

Counselor Toolbox Discussion Group: Attachment Theory

• Attachment theory is a lifespan approach that postulates that people are born with an innate motivational system (termed the attachment behavioral system) that becomes activated during times of actual or symbolic threat, prompting the individual to seek proximity to particular others with the goal of alleviating distress and obtaining a sense of security (bowlby, 1982). A cornerstone of the theory is that individuals build cognitive-affective representations, or “internal working models” of the self and others, based on their cumulative history of interactions with attachment figures (bowlby, 1973; bartholomew and horowitz, 1991). These models guide how information from the social world is appraised and play an essential role in the process of affect regulation throughout the lifespan (kobak and sceery, 1988; collins et al., 2004).

• The majority of research on adult attachment has centered on attachment styles and their measurement (for a review, see mikulincer and shaver, 2007). In broad terms, attachment styles may be conceptualized in terms of security vs. Insecurity. Repeated interactions with emotionally accessible and sensitively responsive attachment figures promote the formation of a secure attachment style, characterized by positive internal working models and effective strategies for coping with distress. Conversely, repeated interactions with unresponsive or inconsistent figures result in the risk of developing insecure attachment styles, characterized by negative internal working models of the self and/or others and the use of less optimal affect regulation strategies (mikulincer and shaver, 2007).

• Although there is a wide range of conceptualizations and measures of attachment insecurity, these are generally defined by high levels of anxiety and/or avoidance in close relationships. Attachment anxiety reflects a desire for closeness and a worry of being rejected by or separated from significant others, whereas attachment avoidance reflects a strong preference for self-reliance, as well as discomfort with closeness and intimacy with others (brennan et al., 1998; bifulco and thomas, 2013). These styles involve distinct secondary attachment strategies for regulating distress – individuals with attachment anxiety tend to use a hyperactivating (or maximizing) strategy, while individuals with attachment avoidance tend to rely on a deactivating (or minimizing) strategy (cassidy and kobak, 1988; main, 1990; mikulincer and shaver, 2003, 2008). Indeed, previous empirical studies indicate that attachment anxiety is associated with increased negative emotional responses, heightened detection of threats in the environment, and negative views of the self (griffin and bartholomew, 1994; mikulincer and orbach, 1995; fraley et al., 2006; ein-dor et al., 2011). By contrast, attachment avoidance is associated with emotional inhibition or suppression, the dismissal of threatening events, and inflation of self-conceptions (fraley and shaver, 1997; gjerde et al., 2004; mikulincer and shaver, 2007).

• Deactivating strategies are used as “flight” reactions from a mother who is seen as emotionally unavailable (main and solomon, 1990). The child learns to hide or suppress the expressions of emotions that the mother does not tolerate (anxiety, fear, anger, or needs of consolation) and deals with threats and dangers autonomously, to avoid the frustration caused by maternal unavailability.

• Conversely, hyperactivating strategies represent “fight” responses to unfulfilled attachment needs, acted when maternal responsiveness appears inconsistent, hesitant, or unpredictable (mikulincer and shaver, 2010): the child tends to amplify proximity seeking strategies to demand or force the mother to pay more attention to him/her (main and solomon, 1990; mikulincer and shaver, 2010).

• Adult attachment style refers to systematic patterns of expectations, beliefs, and emotions concerning the availability and responsiveness of close others during times of distress

Neural basis of attachment-caregiving systems interaction: insights from neuroimaging studies.

• Front psychol. 2015 aug 24;6:1241

• Bowlby (1969, 1988) proposed that caregiving is the result of an organized behavioral system, which is reciprocal to – and evolved in parallel with – the attachment system (george and solomon, 1996, 1999). The caregiving system aim is to promote proximity and comfort when the mother detects internal or external cues associated with situations that she perceives as stressing for the child.

• The maternal caregiving system undergoes its greatest development during the transition to parenthood (pregnancy, birth, and the post-partum period; ammaniti et al., 2014) with striking structural and functional changes, as a result of the large amounts of hormones secreted (panksepp, 1998; mayes et al., 2005). In particular, of greatest importance is the production of oxytocin which seems to motivate and maintain caregiving behaviors, strengthening maternal sensitivity to infant affective cues (frewen and lanius, 2006; kinsley and lambert, 2006; rilling, 2013; mah et al., 2015).

• A mother’s capacity to regulate her child’s emotions is crucial to his/her ultimate feeling of security (ainsworth et al., 1978; lyons-ruth and spielman, 2004). These processes are sustained by maternal sensitivity, i.e., the ability to understand the infant’s feelings in order to respond to them in an appropriate way (ainsworth, 1967, 1973; ainsworth et al., 1978).

• When the mother proves not to be physically or emotionally available security is not attained and negative representations of the self and the other are formed (e.g., doubts about self-worth and worries about others’ intentions).

Depressed parents' attachment: effects on offspring suicidal behavior in a longitudinal family study.

• J clin psychiatry. 2014 aug;75(8):879-85

• Insecure avoidant, but not anxious, attachment in depressed parents may predict offspring suicide attempt. Insecure parental attachment traits were associated with impulsivity and major depressive disorder in all offspring and with more severe suicidal behavior in offspring attempters

Parent-child attachment and emotion regulation.

• New dir child adolesc dev. 2015 summer;2015(148):31-45.

• Insecure attachment during infancy predicts greater amygdala volumes in early adulthood

• J child psychol psychiatry. 2015 may;56(5):540-8

• Greater amygdala volume is associated with increased fearfulness soc cogn affect neurosci. 2010 dec; 5(4): 424–431

Genetic and environmental influences on adolescent attachment.

• J child psychol psychiatry. 2014 sep;55(9):1033-41

• Twin study

• Genes may play an important role in adolescent attachment and point to the potentially distinct aetiological mechanisms involved in individual differences in attachment beyond early childhood.

• Approximately 40% heritability of attachment and negligible influence of the shared environment

Annual research review: attachment disorders in early childhood–clinical presentation, causes, correlates, and treatment

• J child psychol psychiatry. 2015 mar;56(3):207-22.

• Reactive attachment disorder (rad) indicating children who lack attachments despite the developmental capacity to form them.

• Core features of rad in young children include the absence of focused attachment behaviors directed towards a preferred caregiver, failure to seek and respond to comforting when distressed, reduced social and emotional reciprocity, and disturbances of emotion regulation, including reduced positive affect and unexplained fearfulness or irritability.

• “pathogenic care” in dsm-iv and “parental abuse, neglect or serious mishandling” in icd-10 was replaced by “insufficient care” in dsm-5 in order to emphasize that social neglect that seems the key necessary condition for the disorder to occur

Annual research review: attachment disorders in early childhood–clinical presentation, causes, correlates, and treatment

• J child psychol psychiatry. 2015 mar;56(3):207-22.

• And disinhibited social engagement disorder(dsed) indicating children who lack developmentally appropriate reticence with unfamiliar adults and who violate socially sanctioned boundaries.

• Inappropriate approach to unfamiliar adults and lack of wariness of strangers, and a willingness to wander off with strangers. In dsed, children also demonstrate a lack of appropriate social and physical boundaries, such as interacting with adult strangers in overly close proximity (experienced by the adult as intrusive) and by actively seeking close physical contact. By the preschool years, verbal boundaries may be violated as the child asks overly intrusive and overly familiar questions of unfamiliar adults

• Dsed includes socially disinhibited behavior that must be distinguished from the impulsivity that accompanies adhd

• Tying the phenotype to grossly inadequate caregiving was retained in dsm-5 for the important reason that children who have williams syndrome — a chromosome 7 deletion syndrome – have been reported to demonstrate phenotypically similar behavior to those with dsed

• Dsed is predictive of functional impairment, difficulties with close relationships, and more need for special education services

• Lyons-ruth and colleagues (2009), on the other hand, showed that indiscriminate behavior was present in high-risk, family reared infants only if they had been maltreated or if their mothers had had psychiatric hospitalizations. They also found that mothers’ disrupted emotional interactions with the infant mediated the relationship between caregiving adversity and indiscriminate behavior

Although the majority of maltreated children and children raised in institutions have insecure or disorganized attachments to biological parents or institutional caregivers (carlson et al., 1989; o’connor et al., 2003; vorria et al., 2003; zeanah et al., 2005), most do not develop attachment disorders (boris et al., 2004; gleason et al., 2011; zeanah et al., 2004). This raises the question of vulnerability and perpetuating factors

Attachment style predicts affect, cognitive appraisals, and social functioning in daily life

• Front psychol. 2015; 6: 296.

• Participants’ momentary affective states, cognitive appraisals, and social functioning varied in meaningful ways as a function of their attachment style.

• Those holding a secure style reported greater feelings of happiness, more positive self-appraisals, viewed their current situation more positively, felt more cared for by others, and felt closer to the people they were with individuals with an anxious attachment, as compared with securely attached individuals, endorsed experiences that were congruent with hyperactivating tendencies, such as higher negative affect, stress, and perceived social rejection. By contrast, individuals with an avoidant attachment, relative to individuals with a secure attachment, endorsed experiences that were consistent with deactivating tendencies, such as decreased positive states and a decreased desire to be with others when alone.

• The findings support the ecological validity of the asi and the person-by-situation character of attachment theory.

• Anxious (or preoccupied) attachment is associated with more variability in terms of positive emotions and promotive interactions (a composite measure of disclosure and support; tidwell et al., 1996), lower self-esteem (pietromonaco and barrett, 1997), greater feelings of anxiety and rejection, as well as perceiving more negative emotions in others (kafetsios and nezlek, 2002). In contrast, compared to secure attachment, avoidant (or dismissing) attachment has been associated with lower levels of happiness and self-disclosure (kafetsios and nezlek, 2002), lower perceived quality of interactions with romantic partners (sibley and liu, 2006), a tendency to differentiate less between close and non-close others in terms of disclosure (pietromonaco and barrett, 1997), and higher negative affect along with lower positive affect, intimacy, and enjoyment, predominantly in opposite-sex interactions (tidwell et al., 1996).

• Anxious participants approached their daily person-environment transactions with amplification of distress (e.g., higher negative affect, greater fear of losing control, higher subjective stress), decreased positive affect, and greater variability in the experience of negative affect. Anxiously attached participants endorsed more negative and less positive appraisals about themselves

• Avoidant ones endorsed a stronger preference for being alone when with others and a decreased desire to be with others when alone. Additionally, relative to their secure peers, they tended to approach their person-environment transactions with decreased happiness and less positive views of their situation, but not with amplification of negative states. Avoidant participants also felt less cared for by others and less close to the people they were with. Avoidant individuals also reported more negative views of themselves

• Manifestation of attachment styles depends on the subjective appraisal of the closeness of social contacts, rather than on the simple presence of social interactions. The finding that it is social appraisals, not simply social contact, that interacts with attachment is compatible with the description of attachment as a “person by situation” interactionist theory

• The affective states, situation appraisals, coping capacities, and social functioning of the anxious group worsened as closeness diminished; when in the presence of people they do not feel close to, anxious people’s preoccupation with rejection and approval is amplified and this permeates their subjective experiences.

• Attachment styles predicted individual’s subjective experiences across the range of situations they encountered during the week, and not only those that were interaction-based, suggests that attachment styles are relevant features of personality functioning that have pervasive effects on how individuals experience their inner and outer worlds

Infant attachment security and early childhood behavioral inhibition interact to predict adolescent social anxiety symptoms.

• Child dev. 2015 mar-apr;86(2):598-613

• Insecure attachment and behavioral inhibition (bi) increase risk for internalizing problems

• The interaction of attachment and bi significantly predicted adolescent anxiety symptoms, such that bi and anxiety were only associated among adolescents with histories of insecure attachment

Attachment classification, psychophysiology and frontal eeg asymmetry across the lifespan: a review

• Front hum neurosci. 2

• Insecure attachment is related to a heightened adrenocortical activity, heart rate and skin conductance in response to stress, which is consistent with the hypothesis that attachment insecurity leads to impaired emotion regulation. Research on frontal eeg asymmetry also shows a clear difference in the emotional arousal between the attachment groups evidenced by specific frontal asymmetry changes.015 feb 19;9:79

Attachment and eating disorders: a review of current research

• Int j eat disord. 2014 nov;47(7):710-7. Doi: 10.1002/eat.22302. Epub 2014 may 23

• Those with eating disorders had higher levels of attachment insecurity and disorganized mental states. Lower reflective functioning was specifically associated with anorexia nervosa. Attachment anxiety was associated with eating disorder symptom severity, and this relationship may be mediated by perfectionism and affect regulation strategies. Type of attachment insecurity had specific negative impacts on psychotherapy processes and outcomes, such that higher attachment avoidance may lead to dropping out and higher attachment anxiety may lead to poorer treatment outcomes

Eating disorders in adolescence: attachment issues from a developmental perspective.

• Front psychol. 2015 aug 10;6:1136

• The high incidence of the unresolved attachment pattern in eating disorder samples is striking, especially for patients with anorexia nervosa. Interestingly, this predominance of the unresolved category was also found in their mothers.

A review on attachment and adolescent substance abuse: empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment

• Subst abus. 2015;36(3):304-13.

• Strong evidence for a general link between sud and insecure attachment.

• Data on connections between different patterns of attachment and sud point to disorganized and externalizing pathways.

• Evidence suggests that fostering attachment security might improve the outcome

Transitions in friendship attachment during adolescence are associated with developmental trajectories of depression through adulthood.

• J adolesc health. 2016 mar;58(3):260-6.

• The growth model indicated that adolescents who reported a stable-secure attachment style had lower levels of depression symptoms during adulthood than those individuals who transitioned from secure-to-insecure, from insecure-to-secure, or were in the stable-insecure group. Interestingly enough, individuals in both the attachment transition groups had a faster declining rate of depression symptoms over time compared to the two stability groups.

Adult attachment style as a risk factor for maternal postnatal depression: a systematic review.

• Bmc Psychol. 2014 dec 18;2(1):56

• Attachment and pnd share a common aetiology and that ‘insecure adult attachment style' is an additional risk factor for pnd. Of the insecure adult attachment styles, anxious styles were found to be associated with pnd symptoms more frequently than avoidant or dismissing styles of attachment.

Perinatal depression and patterns of attachment: a critical risk factor?

• Depress res treat. 2015;2015:105012

• Prevalence of “fearful-avoidant” attachment style in perinatal depression group

• The severity of depression increases proportionally to attachment disorganization; therefore, we consider attachment as both an important risk factor as well as a focus for early psychotherapeutic intervention

Attachment and health-related physiological stress processes.

• Curr opin psychol. 2015 feb 1;1:34-39.

• People who are more securely attached to close partners show health benefits, but the mechanisms underlying this link are not well specified. We focus on physiological pathways that are potential mediators of the connection between attachment in childhood and adulthood and health and disease outcomes. Growing evidence indicates that attachment insecurity (vs. Security) is associated with distinctive physiological responses to stress, including responses involving the hpa, sam and immune systems, but these responses vary with type of stressor (e.g., social/nonsocial) and contextual factors (e.g., partner's attachment style). Taking this more nuanced perspective will be important for understanding the conditions under which attachment shapes health-related physiological processes as well as downstream health and disease consequences.

Adolescent insecure attachment as a predictor of maladaptive coping and externalizing behaviors in emerging adulthood.

• Attach hum dev. 2014;16(5):462-78

• Qualities of both preoccupied and dismissing attachment organization predicted self-reported externalizing behaviors in emerging adulthood eight years later, but only preoccupation was predictive of close-peer reports of emerging adult externalizing behavior. Maladaptive coping strategies only mediated the relationship between a dismissing stance toward attachment and future self-reported externalizing behaviors.

The relationship between adult attachment style and post-traumatic stress symptoms: a meta-analysis.

• J anxiety disord. 2015 oct;35:103-17

• Adult attachment plays a role in the development and perseverance of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (ptsd)

• Attachment categories comprised of high levels of anxiety most strongly related to ptsd symptoms, with fearful attachment displaying the largest association

The relation between insecure attachment and posttraumatic stress: early life versus adulthood traumas

• Psychol trauma. 2015 jul; 7(4): 324–332.

• Insecure attachment may be an especially important risk factor for ptsd in older adulthood given the critical role of interpersonal relationships to well-being among older individuals

• Results showed that higher attachment anxiety and avoidance predicted greater ptsd symptom severity after controlling for other individual difference measures associated with elevated ptsd symptoms including neuroticism and event centrality.

• A significant interaction between the developmental timing of the trauma and attachment anxiety revealed that the relation between ptsd symptoms and attachment anxiety was stronger for individuals with current ptsd symptoms associated with early life traumas compared to individuals with ptsd symptoms linked to adulthood traumas.

• Individuals with greater attachment anxiety reported stronger physical reactions to memories of their trauma and more frequent voluntary and involuntary rehearsal of their trauma memories. These phenomenological properties of trauma memories were in turn associated with greater ptsd symptom severity

• Factors underlying the relation between attachment anxiety and ptsd symptoms vary according to the developmental timing of the traumatic exposure

• Percentage of variance in ptsd symptoms explained by insecure attachment doubled among older adults with current ptsd symptoms related to early life traumas compared to those who reported symptoms linked to traumas encountered in adulthood.

Interpersonal trauma, attachment insecurity and anxiety in an inpatient psychiatric population.

• J anxiety disord. 2015 oct;35:82-7

• Interpersonal trauma has an impact on insecure attachment and anxiety

• Attachment may play a mediating role between traumatic events and psychopathology

• Interpersonal trauma was correlated to attachment avoidance but not to attachment anxiety

Attachment and social cognition in borderline personality disorder: specificity in relation to antisocial and avoidant personality disorders.

• Personal disord. 20

• Attachment insecurity is believed to lead to chronic problems in social relationships, attributable, in part, to impairments in social cognition, which comprise maladaptive mental representations of self, others, and self in relation to others. However, few studies have attempted to identify social-cognitive mechanisms that link attachment insecurity to bpd and to assess whether such mechanisms are specific to the disorder. For the present study, empirically derived indices of mentalization, self-other boundaries, and identity diffusion were tested as mediators between attachment style and personality disorder symptoms. In a cross-sectional structural equation model, mentalization and self-other boundaries mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and bpd. Mentalization partially mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and antisocial personality disorder (pd) symptoms, and self-other boundaries mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety.15 jul;6(3):207-15

Lower oxytocin plasma levels in borderline patients with unresolved attachment representations.

• Front hum neurosci. 2016 mar 30;10:125

• Bpd patients with unresolved (disorganized) attachment representations had baseline ot plasma levels which were significantly lower than in bpd patients with organized attachment representations

• Altered ot regulation in bpd as a putative key mechanism underlying interpersonal dysregulation

Adult attachment ratings (aar): an item response theory analysis

• J pers assess. 2014 jul-aug; 96(4): 417–425

• One of the major goals in our own research on pds has been to investigate the reciprocal relationships between interpersonal attachments and emotion regulation, especially in patients with borderline personality disorder (bpd). Our general hypothesis is that many of the interpersonal behaviors of persons with bpd can be understood as frustrated (and frustrating) bids for attachment as they cope with frequent episodes of emotion dysregulation. These attempts at coping result in self-defeating efforts to secure the usual provisions of attachment—a secure base in general and a safe haven in times of acute distress, reflected in proximity-seeking to attachment figures and separation distress when apart.

• Document the importance and specificity of problems in attachment for patients with bpd

The nature of attachment relationships and grief responses in older adults: an attachment path model of grief.

• Plos one. 2015 oct 13;10(10):e0133703.

• Higher levels of avoidant attachment reported less emotional responses and less non-acceptance.

• Individuals who reported higher levels of anxious attachment reported greater emotional responses and greater non-acceptance.

• These relationships were mediated by yearning thoughts.

• Grief therapy may be organized according to individual differences in attachment representations.

Attachment styles, grief responses, and the moderating role of coping strategies in parents bereaved by the sewol ferry accident

• Eur j psychotraumatol. 2017; 8(sup6): 1424446.

• Anxious attachment was associated with severe shame/guilt, and avoidant attachment correlated with complicated grief. Anxious attachment was positively associated with all types of coping strategies, and avoidant attachment was negatively related to problem- and emotion-focused coping. The use of problem-focused coping strategies was a significant moderator of the relationship between the avoidant attachment dimension and shame/guilt. Avoidant attachment had a significant effect on shame/guilt in groups with a high level of problem-focused coping. In contrast, none of the coping strategies significantly moderated the relationship between anxious attachment and grief response.

• The results suggest that people with highly avoidant attachment might be overwhelmed by shame and guilt when they try to use problem-focused coping strategies.

Attachment and chronic pain in children and adolescents

• Children (basel). 2016 dec; 3(4): 21

• It has been proposed that an individual’s characteristic attachment behaviors are likely to be activated as a result of an illness or threat [16]. Illness, and arguably pain, may trigger an increased need for security and the wish for a close, caring other. This may be an adaptive response within the context of an injury or acute pain. However, in the context of chronic pain this can result in a range of complex and difficult behavioral interactions.

• Attachment styles characterized by avoidance of emotional expression (e.g., insecure-avoidant, dismissing and fearful styles, or type a attachment strategy) may predispose individuals to chronic pain conditions [35]. Children with this attachment style may have parents who respond to expressions of negative affect, including pain, by either withdrawing from their child or responding with displeasure or anger [35]. Children learn to inhibit verbal or nonverbal signs of distress, because they have found these to serve no useful protective function [23]. Attachment styles that are defined by excitatory self-protective mechanisms (i.e., insecure-ambivalent, preoccupied or type c attachment strategies) are also likely to have implications for pain experiences. Children with this style may have parents who respond unpredictably. Consequently, the child may alternate between signaling various exaggerated expressions of negative affect (e.g., fear, anger, desire for comfort), with the aim of trying to get their unpredictable parent to respond [35]

• Attachment deactivating and hyperactivating strategies contributing to dysregulation of the stress system within the body, and subsequently contributing to pain sensitivity.

• In certain circumstances, the attachment figure in this caregiving environment may tolerate pain (owing to it being understood as a physical symptom) as an acceptable signal of distress compared to fear, anger or sadness [46]. In these circumstances, signaling of pain may elicit a caregiving response serving to reinforce the behavior for any experienced distress

• Lower trust and satisfaction with their physician [82], greater use of emotion-focused coping and less problem-focused coping [81], lower perceived social support [83], greater pain intensity and disability [14], greater pain-related distress [84], more physical symptoms [12], especially medically unexplained symptoms [13], and higher levels of pain-related stress, anxiety, depression and catastrophizing

• Meredith et al.’s [53] attachment-diathesis model of chronic pain, attachment-related primary appraisals of pain interact with secondary appraisals of the self (as equipped or not to cope; worthy or not of social support [56]) and of others (as available and adequate to provide effective support [57]) [52]

• Insecurely attached individuals may be: (1) less able to manage the distress associated with pain; (2) more likely to use emotion-focused rather than problem-focused coping strategies; (3) less able to procure and maintain external supports; (4) less able to form therapeutic alliances; (5) less likely to adhere to treatment recommendations; or (6) more likely to evoke and perceive more negative responses from health professionals [53]

• The process of actively seeking support inherently relies on an individual’s comfort with closeness to others, the belief that the self is worthy of support and that others are available t

• There are three possible treatment targets in attachment-based treatments with adolescents: (1) modifying the adolescent’s internal working model of self or others (especially their caregiver); (2) modifying the caregiver’s internal working model of self or others (especially their adolescent); and (3) promoting emotionally attuned communication between the caregiver and adolescent [80]o provide it [63]

• The caregiver’s ability to maintain a cooperative partnership with an adolescent is likely to be dependent on the caregiver’s ability to monitor their own emotions, clearly asserting their own positions, while validating and supporting the adolescent’s attachment and autonomy needs [79]

Emotion regulation as a mediator in the relationship between attachment and depressive symptomatology: a systematic review.

• J affect disord. 2015 feb 1;172:428-44

• Emotion regulation is a mediator between attachment and depression. Hyperactivating strategies, in particular, have been consistently noted as mediators for anxious attachment and depressive symptomatology, whereas evidence for deactivating strategies as mediators between avoidant

Attachment based treatments for adolescents: the secure cycle as a framework for assessment, treatment and evaluation.

• Attach hum dev. 2015;17(2):220-39

• Cyclical processes that are required to maintain a secure attachment bond. This secure cycle incorporates three components: (1) the child or adult's iwm of the caregiver; (2) emotionally attuned communication; and (3) the caregiver's iwm of the child or adult